The war isn’t over when the bombs stop falling

It’s a low building set apart. Vientiane leaves it there, in an area that feels peripheral and central at once: far enough from the flow, close enough that you can’t pretend it isn’t there. You reach it on foot, on your own steps. A few minutes from the main road. No shortcuts. And maybe that’s the point: those steps are the only warning you allow yourself.

You slide open the small door and ask permission to enter. The first thing you notice is the silence. A silence chosen, constructed, and yet natural. A place that doesn’t raise its voice, doesn’t chase effects, doesn’t grab you by the throat. No drama. No rhetoric. It places you in front of a simple truth—almost banal, and for that reason unbearable: time doesn’t heal everything if what you left in the ground can still explode.

A legacy that refuses to become the past

Between 1964 and 1973, during the war in Indochina—in what was called the Secret War—Laos was hit by a quantity of ordnance that is hard to even picture today: over two million tons, according to estimates still widely cited. [1]

Put that way, it’s just a number. Two billion kilograms. Too large to fit in the mind, so it slips away. The real scale risks becoming abstract, distant, almost harmless. And then you reach the core of the problem: a significant portion did not detonate. And what didn’t explode then did not stay in the past. It stayed here.

Laos is often described as the most heavily bombed country in the world per capita. [2] But statistics alone explain nothing. They’re a label, not a life.

Real life is the invisible geography those numbers contain: fields that aren’t ploughed, paths avoided, children taught what not to touch. Rural communities living with a practical, everyday question that should not exist: is this land really mine, or does it still belong to the war?

The “bomb” as an everyday object

Inside the COPE Visitor Centre in Vientiane [3] you realise that, unlike many places of memory, the object here is not a fetish: it is evidence. It is trace. It is consequence. It isn’t a museum in the classic sense. It doesn’t display—it shows, and it proves.

And it does so without raising its voice. In the silence of ordnance waiting in the ground, and in the blast of what has already exploded. Legs, hands, bodies. Lives.It sits at the point of contact between two worlds: memory and everyday life. Its mission is concrete: to support access to physical rehabilitation services in Laos for people with mobility disabilities. Everything else—the context, the history, the whys—hits you like a dull thud, without the need for shocking images. And as you wander through those rooms, the one sentence that keeps returning is always the same: the war isn’t over when the bombs stop falling.

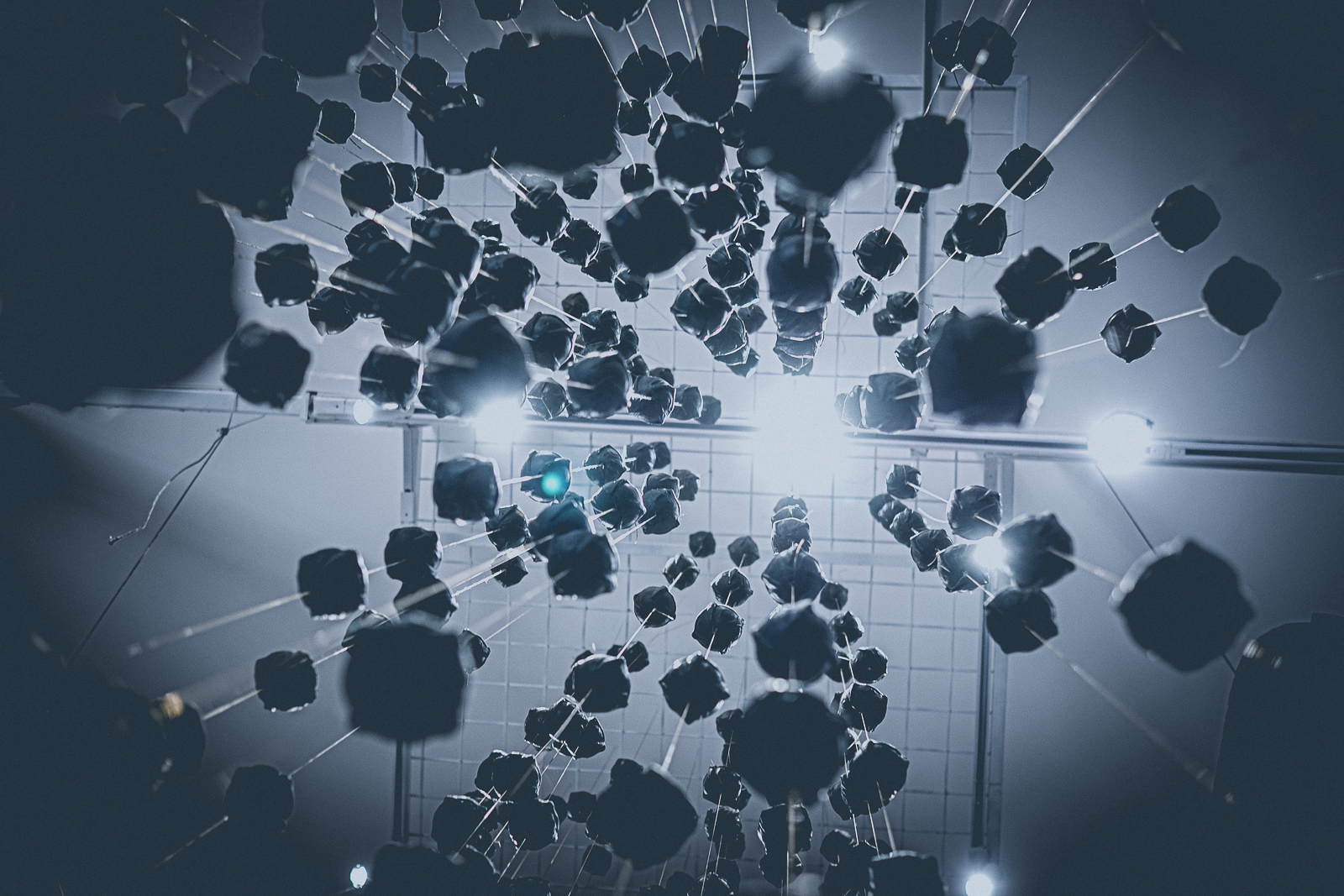

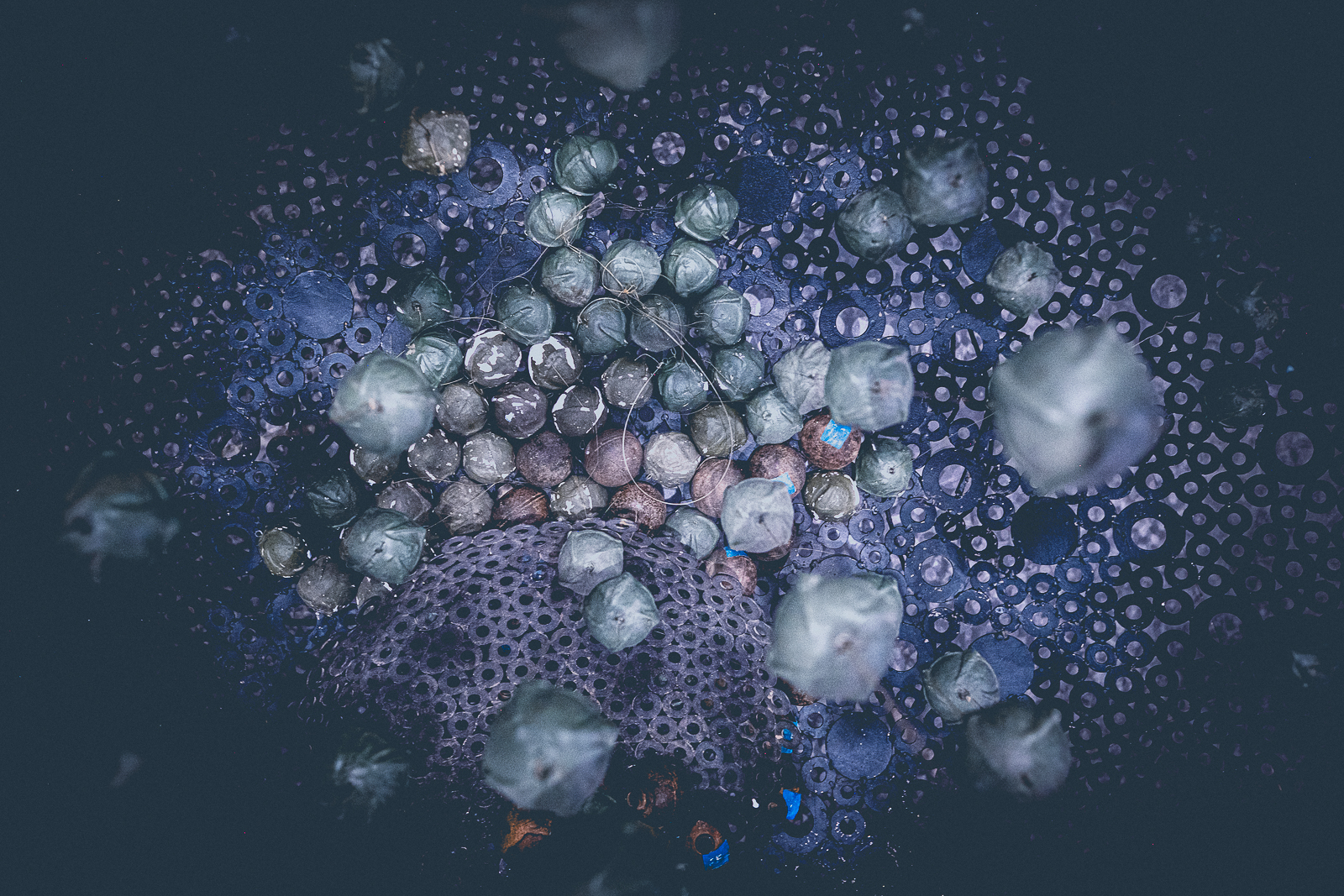

Handmade prosthetics, shaping a reality that is heavy, but still tries to stand. Cluster bombs, suspended, multiplied, almost forming an artificial sky. This is not the spectacle of horror: it is the hardest idea to digest—normalisation. Ordnance designed to open and scatter. A technical gesture, serial, anonymous. A geometry that, once it stays underground, becomes destiny. And then you understand that post-war here means something else: not an “after”, but a “during” that has already lasted for decades.

Numbers that never close a story

Accidents from explosive remnants of war still happen today. Even when they are “few” on a global scale, they are too many for a country that has already paid the highest price of an absurd war—by reasons, by dynamics, by proportions.

The point isn’t to update a bulletin. The point is to understand the nature of these wounds. Because this isn’t only about death or survival: it is about mobility, work, school, independence. It is about the future. And freedom. And that is where COPE becomes essential: it doesn’t simply commemorate, as so often happens. It holds together the missing piece of the word Reconstruction in a foreign war that ended more than fifty years ago.

Repairing the future, one body at a time

COPE works on the side that often falls outside the narrative: life after. Prosthetics, orthotics, rehabilitation, assistance. A network that allows someone who has lost a part of themselves to reclaim the possibility of moving through the world—physically and socially.

In a country that turns national pride into an open-air museum, the message shifts here: from tragedy to responsibility, from responsibility to choice. Because the existence of a place like this proves two opposite things at once: that the legacy of the war is still active; and that there are people who, every day, quietly disarm it—not only in the soil, but in lives. Even in 2026. Even more than fifty years later.

The question that remains open

It’s impossible to walk out of this story without asking: who should be at the front line?

Today the United States, as the primary party responsible, is also among the main international donors for the UXO sector in Laos, with contributions amounting to hundreds of millions of dollars over several decades, and programmes focused on clearance, risk education, and victim assistance. This fact exists, it is real, and it deserves to be acknowledged. [4]But the moral question is not cancelled by financial data. It turns into a question of proportion: is it enough, compared to the scale of the problem? Enough, compared to the time? And above all: enough, compared to what this contamination still prevents—development, safety, the freedom to live on one’s own land? Fifty years on, with all the technology available, Laos remains one of the countries most contaminated by cluster munition remnants. [5] And that alone is a sentence that should not exist.

A conclusion without rhetoric

This place—a small room behind a small sliding door—doesn’t ask you to cry. It asks something far harder: to stay lucid.

It makes you understand that war is not an event that ends with a signature or with a date in textbooks and newspapers. Sometimes war is a small object in the ground, a wrong gesture, a field left unworked, a missing leg, a prosthesis that sets a life in motion again.

And yet—even inside the damage—there are people who have chosen to deal with it. Who repair. Who rehabilitate. Who stitch back together, not history, but the possibility of living.The war isn’t over when the bombs stop falling.

It ends when the ground stops being an enemy.

And when memory stops being an exhibition and returns to being responsibility.You slide open that small door again and walk away from the silent place exactly as you found it. A cigarette, and the temptation to file it all away as a Laos chapter: one of the many appendices of the American war, as they still call it around here, in Indochina.

But then the numbers return. And the detail changes everything: Laos is not an exception. In 2026, contaminated ground still exists in around sixty countries and territories—within wars that are still active. Languages change. The problem doesn’t.

The question remains.

References

[1] https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/2022-10/UXO%20Project%20Document%202022-2026_countersigned.pdf

[2] https://www.halotrust.org/where-we-work/asia/laos/

[3] https://copelaos.org/

[4] https://la.usembassy.gov/u-s-and-norway-province-over-20-8-million-to-increase-uxo-survey-and-clearance-in-southern-laos/

[5] https://www.clusterconvention.org/cluster-munition-legacy-in-lao-pdr-50-years-on/